Added to cart

While we are called The RAF Bradwell Bay Preservation Group with the aim of preserving the rich history of RAF Bradwell Bay during World War 2. However, the RAF arrived in Bradwell on Sea before the start of the war in the form of RAF Dengie Flats. RAF Dengie Flats was a grass airfield built to service the Dengie Flats Firing and Bombing Range. So, the history of Bradwell Bay starts before the building of the large fighter station known as RAF Bradwell Bay and continues long after the fighter station closed at the end of November 1945.

The Air Ministry had proposed a firing and bombing range on the Dengie mud flats as far back as 1925. There was much protest from local people as to how much this would affect farming and fishing in the area. A petition signed by the owners and occupiers of the marsh farms which would be particularly affected by the proposed scheme, has this week been sent to the Ministry. This petition sets out the various strong objections to the scheme and certainly demands the serious consideration of the authorities. The protests worked and the building of the range was postponed.

In financial terms the Air Ministry were probably not disappointed as this was a financially difficult time and the RAF were in a disbandment phase. Since the end of the Great War the RAF had been run down from a total of 188 squadrons to 33 squadrons. Personnel had decreased from a wartime strength. The army and navy were trying to get what was left to be returned to their parent service. Lord Trenchard fought hard to retain the Royal Air Force as an independent service. He knew that air power would be a most important factor in any future difficulties. He was supported in this by Winston Churchill.

But, the changing politics of Germany and consequent threat of a European war, made the expansion of the RAF necessary. New personnel would need training, aircrew would need to practice firing aircraft guns and bombs. Therefore, the Dengie Flats firing and bombing range was resurrected.

In 1936 the air ministry purchased land from Weymark’s Farm and Downhall Farm in order to build a grass strip for aircraft to land for refuelling and re-arming. The airstrip also became the base for the range staff which consisted of 30 Airmen and a sergeant. An officer did come from RAF North Weald occasionally, staying at the Green Man Inn rather than in the barracks.

The planning of the range and airfield was a major project. The land for the airstrip had to be fenced off and the land ploughed and planted with grass seed.

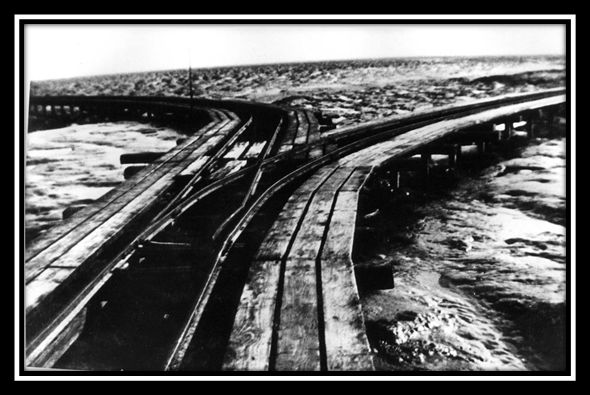

The construction of the range presented more problems than the airstrip construction. A track had to be built which across the flats which diverged to the north and south, at the respective ends of the tracks were platforms which held the targets. Narrow gauge railway tracks were built to enable repairs to be carried out. Barges carrying steam hammers were used to drive piles in.

This was a major engineering project due to the thick mud of the Dengie Peninsula coastline and the tidal range of the area. This construction needed to be sturdy as it was continually battered by the tidal sea and of course stray ammunition. In his book Narratives of War by Jim Bye (published by the Burnham Museum) he states:

When completed it was possible to walk along the tracks, even at normal high tides. Sometimes the waters would lap onto it just a little, it was then that your realised how accurate the builders were for as far as one could see, the track was completely level, it was a real achievement.

Each track ended in a platform on which were built pyramid shapes, painted yellow as target guides. The railway tracks enabled the targets to be reached for maintenance. The targets were damaged by stray munitions of well as the environmental effects of the sea and its tides.

The firing range had three observation towers, the 2 towers near to St Peters Chapel and Howe outfall were wooden, the main control at Sandbeach was more strongly constructed.

One remaining piece of RAF Dengie Flats is the station name board, which is in the possession of The RAF Bradwell Bay Preservation Group and is ready to be displayed in our museum.

Having looked at the construction of the range, it was planned to open on 1st August 1937. Like most projects it fell behind and was finally completed and operational in late 1938.

Photographs are courtesy of the Kevin Bruce Collection.

The airstrip and base formed RAF Dengie Flats. Jim Bye in his book Narratives of War, who was to be based at RAF Dengie Flats and later at RAF Bradwell Bay, described the airstrip as having a rectangle of military huts. The accommodation hut was a large room which housed the other ranks with divisions for two corporals and a sergeant. The sergeant would be the officer in charge of the base. The shower and ablution block formed another side of the rectangle. This also had a games room. The cookhouse and dining room formed another side of the rectangle. The cookhouse had a massive coal fired cooking range; its coal consumption would have caused some concern in these green aware days. The final side of the rectangle was the guardhouse. The most important item of equipment appears to be the dartboard on the back of the door, apparently many tiny holes was proof that accuracy was not a strong point.

The base defence was kept in the guard room in the form of 2 WW1 Lee Enfield rifles. There was a table and chairs together with the base notice board. 2 Very Pistols, much used, were hung by their trigger on hooks.

Across a concrete road, away from the accommodation, was further three huts. One was a petrol store, another an armoury with ammunition and practise bombs. The third hut housed the generator, at this time the village of Bradwell on Sea did not have an electrical supply, in 2025 it does not have a gas supply.

In an article in the Essex Countryside in February 1971 ROGER FRESCO-CORBU. (ex-Flight Lieutenant R.A.F.V.R.) wrote:

The " station " at that time consisted of a large hut which combined sleeping quarters and cookhouse and a small hut which served as guardroom. The personnel were composed of a sergeant (an R.A.F. regular), who was the " C.0.” two elderly class E reservists, a very fat and jovial cook, a driver and about a dozen assorted airmen who were mostly air-crew volunteers. On odd occasions a junior officer would arrive from North Weald, book in at the Green Man, visit the camp and then return whence he had come.

Our duties, apart from guards, were not clearly defined. The guarding was done round the clock with rifles for which ammunition had not at that time been supplied. In fact, the total firepower of R.A.F. Bradwell consisted of the sergeant's revolver, which with a few rounds of ammunition was securely locked in the guard-room safe. With this formidable, arsenal we were presumably expected to repel invaders or prevent an airborne landing.

Occasionally the marshes by the sea wall were used as an air-to-ground firing range by fighters from various 11 Group stations. We would then man a watchtower and scan the countryside through binoculars to spot people and. stop them from entering the danger zone. There were never any people to stop,

When things got tough across the Channel and the German armies started their rampage through France, we were ordered to manhandle a varied collection of old vehicles across the airfield in order to prevent any unauthorized landings.

In the evenings those not on duty would take a short cut over the fields to the ancient Green -Man inn for a beer and a singsong accompanied on the piano-accordion by the landlord’s talented daughter, [Betty Bruce]

It was a peaceful life and a very fine spring. For some it was the first experience of spring in the country. One of our favourite occupations was to take long walks along the quiet roads and lanes of this beautiful countryside, with the tang of the sea never far away. This idyllic existence ended for me in the early days of June when I was posted back to North Weald for onward transmission and the business of getting on with the war. I shall, however, always treasure the memory of that first spring of the war spent in this very delightful part of rural Essex.

Co-ordination of booking the range was carried out by 11 group fighter command headquarters. Group would telephone the airstrip each morning giving the squadrons and numbers of flights. The range crew would set off early by lorry to their allocated duties. Sometimes the weather would deteriorate, and all activity would be cancelled. One airman was taken to the two towers, at St Peters and Howe, or as near as the lorry could get and walking the rest. One of their duties was to ensure that members of the public did not use the footpath whilst the range was in use. I do wonder if they were instructed to be polite such as I say old chap would you mind going back as we are using the firing range? Or was more colloquial RAF language was used? My imagination tells me probably the latter!

The central control point was manned by 4 airmen and a safety officer. The safety officer was required to have flying experience and manned the radio with the call sign Group Guard One. The four airmen manned 3 of the block houses, one airman would be in the quadrant tower. One airman was in communication with the range safety officer and give the results of the firing or bombing. Bombing was not a frequent exercise but the air to firing range was almost a daily occurrence.

Co-ordination of booking the range was carried out by 11 group fighter command headquarters. Group would telephone the airstrip each morning giving the squadrons and numbers of flights. The range crew would set off early by lorry to their allocated duties. Sometimes the weather would deteriorate, and all activity would be cancelled. One airman was taken to the two towers, at St Peters and Howe, or as near as the lorry could get and walking the rest. One of their duties was to ensure that members of the public did not use the footpath whilst the range was in use. I do wonder if they were instructed to be polite such as I say old chap would you mind going back as we are using the firing range? Or was more colloquial RAF language was used? My imagination tells me probably the latter!

The bureaucracy was very intensive local bylaws had to be changed to military byelaws giving the RAF powers to exclude people from the area both on land and at sea. The military powers being invoked were the Military Lands acts of 1892 and 1900 as applied by the Air Force order of 1918 with the consent of the Board of Trade for regulating to use of the above-named range.

The RAF had to comply with many conditions including notification of the public when bombing and firing was taking place. Red flags were to be displayed on flag staffs. At night a steady red light placed in similar positions. RAF personnel were to be in all the observation towers so that they could turn back members of the public with a warning that they must leave the prohibited area immediately.

RAF Officers, RAF Police, warrant officers and NCOs all had the power to arrest and remove people infringing the byelaws. Infringements could result in a fine of no more than £5 (£415 in 2023). The byelaws also covered the recovery of projectiles, instructions for if projectiles were dredged or trawled up accidentally were instructed to immediately return the projectile in the same state as found into the water.

Only authorised people/vessels could recover projectiles under Naval, Military or Air Force instructions. Fishing in the sea area could take place when the range was not in use, relevant authorities would be notified so that fishing vessels could operate in the sea areas of the range.

If the range was in operation with the relevant flags or lights were displayed and an aircraft or vessel was seen to be in danger, the first action would be to cease any firing of bombing. The same for visitors intruding in the land area. A second red flag or light should also be flown or displayed. This was so that the master or captain of the vessel or aeroplane could see the signal and manoeuvre out of the danger area. The regular signals were to be displayed from 30 minutes before firing/bombing commenced until activity if finished. Firing practise was only allowed during daylight hours, but bombing could be carried out by day or night, although there does not appear to have been any nighttime use of the range.

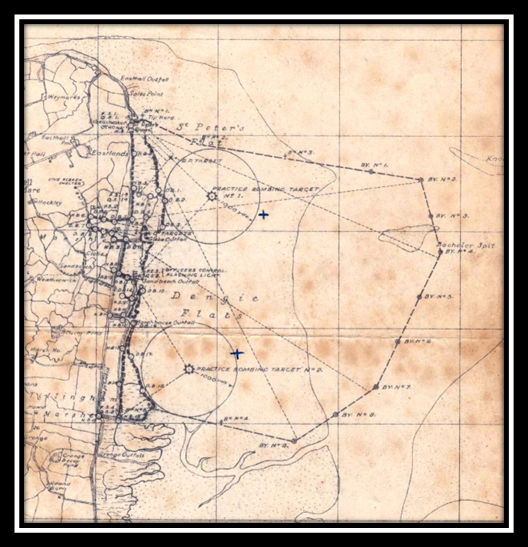

The extent of the range areas was clearly defined in the bylaws for both the sea area and land area, giving instruction for North, South, East and West approaches. This is best demonstrated by the map, attached.

The range was so much in use that sometimes the range staff had to request a lull in firing to allow repairs to be carried out on the range. Although strict safety measures were in place Jim Bye describes an incident in his book Narratives of War (Published by Burnham Museum).

During such a respite I was at one of the targets making an assessment of what was required for making repairs. It was a cold crisp day and just as I had almost finished, I thought I could hear the sound of an aircraft. I looked upwards and scanned the sky, and yes there was an aircraft, he was going into a steep attacking drive, heading straight for the target, for the very spot that I stood on. My inboard computer began to work in top gear and told me to stand still as pilots seldom hit the centre of the target, generally it was somewhere left or right of centre. By this time, he was firing, the continuous stream of bullets cut through the mud a few feet to my right, then the pilot pulled out of his dive and swooped heavenwards. I ran like an Olympic sprinter for the safety of the large blockhouse, firing a red cartridge from my very pilot as I ran, then as the aircraft turned, I fired again and then yet again. The pilot obviously saw the signals for he came in low, waggled his wings and sped off. He was at fault because the cones were not hoisted, but I did not report it and the reason was it was pointless, the RAF take such incidents very seriously and there could have been a court martial. Pilots in 1940 did not need such hassle and I wasn’t hurt.

The range didn’t have a 100% safety record, throughout its existence, and some aircraft were lost including some post war jets. More about the latter days of the range in a later post.

1940

To demonstrate how busy the range was figures for the range use for March, April and May by aircraft type. If anything, these figures are probably underestimated.

March

Hurricanes

85

Spitfires

70

Blenheim’s

6

April

Hurricanes

84

Spitfires

60

Blenheim’s

38

Magister

1

May

Hurricanes

18

Spitfires

53

Blenheim’s

29

Magister

1

Major events of the war included the Dunkirk Evacuation, during this time the flights at Dengie Flats range were paused. This did raise the fear of invasion which the German’s had planned; they named it Operation Sealion. Coastal defences were improved, and RAF Dengie Flats airstrip was covered with old, wrecked cars to prevent gliders landing on the airstrip. Local people were trying to take the leather from the seats.

The Germans knew that they needed to gain air superiority before any attempts at invasion could begin. The Battle of Britain was the Germans trying to destroy the RAF, which although numerically outnumbered had strategy in the form of Dowding’s Plans that led to their defeat. The German switching targets to bombing cities rather than airfields gave the RAF some respite.

It was not long before training restarted on the Dengie Flats firing Range. Many of the pilots using the range went on to serve in the Battle of Britain, for example, Adolf Gysbert Malan, known as Sailor Malan. Malan, from South Africa, had joined the RAF in 1936 learning to fly in Bristol. He went on to become the Squadron Leader of 74 Squadron which was a frequent user of the Dengie Flats flying Range. He Was awarded the DFC and Bar and DSO and Bar.

Adolf ‘Sailor’ Malan was slightly older and more mature than many other fighter pilots. Apart from ability as a flyer he thought that the clue to success was also to be a good marksman and get in close enough to the opposition to ensure a kill. Training at the Dengie Flats Firing range would have been important to him.

While RAF Dengie Flats is often overlooked in favour of the history of RAF Bradwell Bay, it is important in the story of the RAF in Bradwell on Sea. In fact, the Range existed before RAF Bradwell Bay and continued into the 1960’s, long after RAF Bradwell Bay closed on 30th November 1945.

It was inevitable that as aircraft were being pushed to their limits, of by inexperienced pilots that things went wrong. After WW2 use of the range was by jet aircraft both RAF and USAF.

It is sad to note that loss of life and aircraft was a part of training at a bombing and firing range and the Dengie range was no different. There are no records indicating early crashes on the range, but few records were kept of Range activities. The pilot of the Boston Havoc that crashed on the range, William Marshall Poupore, is the only grave from RAF Bradwell Bay in the Churchyard extension of St Thomas Church in Bradwell on Sea.

06th Oct 1942

Boston Havoc

418 Squadron

15th Oct 1945

Mustang 111

309 Squadron

18th Oct 1945

Mosquito XXX

151 Squadron

May 28th 1951

Meteor

226 OCU

June?? 1951

Meteor

226 OCU

26th March 1953

F86-A

USAF

27 August 1957

F-84F

USAF

The Dengie Firing and Bombing range continued to be used even once RAF Dengie Flats had been replaced by RAF Bradwell Bay in 1941. The range was used by squadrons stationed at RAF Bradwell Bay. The new station had its own Range Officer. The range was used throughout WW2 and long after RAF Bradwell Bay closed in November 1945, into the Cold War.

Following the end of the war RAF Bradwell Bay formed 2 A.P.S, that is Armament Practice School, under the command of G.D. Stephenson. The school used the range as its practice area. On 30th November RAF Bradwell Bay closed and 2 A.P.S. moved to RAF Spilsby.

This was not the closure of the range, which did not occur until 25th August 1965. Responsibility for the range was initially passed to RAF Hornchurch then to RAF Martlesham Heath and finally on 1st January 1961 to RAF Wattisham. The use of the range was by the RAF and USAF. It is believed that the USAF had a base in East End Road, but I haven’t seen documentary evidence of this.